Photo Courtesy: NESHL/Facebook

Cars lined the parking lot of Remsen Arena at Choate Rosemary Hall on a brisk January morning in Wallingford, CT. The air was chilly, but an electric buzz grew as athletes climbed out of their vehicles to grab hockey equipment from their trunks.

They lugged oversized wheelie duffle bags and black bucketed sleds across the lot to the warm lobby, rolling in wheelchairs or moving with crutches. They reconnected with teammates and foes sharing stories of weekends and hard-hitting matchups of long ago.

Remsen Arena has hosted many high school and community hockey games since opening in 1967, with some of the best NHL and Olympic players lacing up in its locker rooms. Its storied stage was the perfect locale for a showcase of adaptive sport, with the Northeast Sled Hockey League athletes in the spotlight.

It may look simple, but sled hockey is more complex than just “regular” hockey while sitting down.

First created in Sweden in the 1960s, the sport is adapted for players with physical disabilities or mobility impairments to sit in bucketed sleds. They clench customized half-length hockey sticks fitted with jagged metal “teeth” on the ends, providing momentum and navigation by carving into the ice to propel themselves forward. They play with two sticks – a right and a left. They can even pass the puck from one stick to the other, right under their legs, if they have them.

The goal remains the same - check hard and get the puck in the net by any means necessary.

As the first-ever multi-state co-ed sled hockey league in the United States, the 19 NESHL member clubs stretch as far north as Maine, spread out to the south in Maryland and west to Ohio. The league takes a regional approach to the game, welcoming athletes of all ages and walks of life, ages 15 to 60 and above, to participate in one of its three-tiered divisions.

The NESHL is also a launching point for players to compete on the biggest international stages, with league alumni like David Eustace, Noah Grove, Griffin Lamarre, Kyle Zych, and Jack Wallace securing Paralympic gold for Team USA.

"You're able to bring all these people together under the NESHL and let them express themselves in all different ways on the ice and off the ice," New York Sled Rangers manager Larry Minei said. "Bringing people with disabilities from the entire east coast and out to Ohio together, to be able to have something in common while also fighting for something with each other."

In Wallingford, four teams were set for regular season play in the league's Metropolitan division. The teams headed to their dressing rooms to change into heavy synthetic pads, talk strategy, and don wool hockey jerseys over their chests.

Players filed into the hallway and brought their sleds to the door of the freshly cut ice sheet. They all knew that intrinsic feeling was back again. It was time to drop the puck on another weekend of high-octane action in the NESHL.

The NESHL is…an environment to learn and grow.

The referee blew his whistle for the opening draw between the white and navy blue-clad Northeast Passage Wildcats and the midnight black jerseyed USA Warriors. Chaos ensued. Sticks clashed and clawed, a fight for the faceoff.

The puck escaped the center ice dot and was fed to a Wildcat wearing number seven, Danny Santos. With confidence and poise, he danced with the puck over the blue line and wired a shot into the top shelf of the net to give his squad a quick 1-0 lead.

Santos has always done everything fast, even from birth. Delivered six weeks premature, Santos was born with femoral hypoplasia, a rare congenital disorder that causes underdeveloped or absent femurs.

Off the ice, he’s never without his trusty forearm crutches and a soft-spoken jovial demeanor. But when Santos is strapped into his custom-built sled, his speed and size make him a self-proclaimed “pest” for opponents.

“Being 4-foot-2, you know, 90-something pounds depending on the weekend, [after] desserts and stuff, it's part of my game to use that small size to be quick, shifty,” Santos said. “I'm able to use [the] nose of my sled to angle people off who are double, triple my size.”

Santos plays with a custom sled and half-sticks, giving him the tools to move fast on the ice. (Courtesy: Danny Santos)

Growing up in Merrick, NY, Santos fell in love with adaptive sports in elementary school. He tried sled hockey at nine years old with a local program, the Long Island Roughriders, and took to the game quickly. With his skill and confidence rising, Santos was invited to join USA Hockey’s Player Development Camp in 2006.

“I was the youngest one there at 13 years old, and kind of got to my first taste of the higher level,” Santos said. “I got to meet a lot of new friends from across the country,”

Santos (left) battles at the faceoff dot at USA Hockey’s Player Development Camp. (Courtesy: Danny Santos)

When Santos considered college, he wanted to explore his passion for adaptive sports. Luckily, the Northeastern Passage program, an affiliate of the University of New Hampshire, recruited Santos for its sled hockey student-athlete program, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to continue playing the sport he loved while getting an education.

It was a no-brainer. Santos was going to school in the Granite State.

Founded in 1990 and merged with UNH in 2000, Northeastern Passage provides therapeutic recreation for people with physical, cognitive, emotional, and mobility impairments in local communities and schools.

The program’s student-athletes practice and play adaptive sports regionally on one of NEP’s competitive teams but also experience camaraderie with other young adults who live with impairments.

“It was really a high-level program as well, with guys on the team like Taylor Chase, Kip St. Germain, Joe Howard,” Santos said, proud of teammates who also went on to win Paralympic gold. “A chance to play at this high level while being a student doing my classes, [there was] never time to worry about hotel fees or travel arrangements. It was always covered by NEP.”

NEP houses several sled hockey crews that compete in the NESHL and extend support for other adaptive sports including wheelchair rugby, power soccer, and wheelchair lacrosse. After graduating from college in 2017 and being unsure of his next direction, Santos was offered the opportunity to continue supporting NEP’s mission by joining their staff full-time as a program support assistant.

“It was awesome because my mom was in a position to also [want] to move, so we kind of did it like a team effort,” Santos said. “It's been pretty cool to go from that student-athlete to going to graduate, ‘what do I do next?’, to being able to stay here full time, still play hockey with this program, and do what I do today,” Santos said.

Santos mainly fulfills an administrative role behind the scenes at NEP, while also serving as a coach and mentor for the program's latest group of six student-athletes in sled hockey. Whether he's processing donations, answering phones, filing paperwork, or running drills on the ice, Santos approaches his job with the same smile he had when he first fell in love with adaptive sports.

NESHL commissioner Mike Ciavarro awards the 2018 NESHL Adult A League Trophy to NEP in Exeter, NH. (Courtesy: NESHL)

In addition to his day job with NEP, Santos still plays with the organization's premier NESHL squad, ranking second in team scoring in the 2023-24 season. He also has taken a leadership role as the league’s secretary, applying skills from his day-to-day job to lighten the load on NESHL commissioner Mike Ciavarro’s shoulders.

“The NESHL means a lot to me, it's been a really big part of my life since early high school days,” Santos said. “I'm really grateful for Mike [Ciavarro]’s hard work, and what he does. The league itself has been really impactful.”

The NESHL is…an opportunity for found family.

Before the next game began, the New York Sled Rangers and Gaylord Wolfpack set rivalries aside, huddling at the center red line for a photo.

The athletes looked up to a camera broadcasting the game and frantically waved into the lens.

“We love you Tiger!” the players shouted to Wolfpack teammate, Bobby “Tiger” Jenner, who was watching from his bed in Gaylord Hospital, the sponsor organization of the squad.

Players pose for a photo at center ice, sending their best wishes to Bobby “Tiger” Jenner. (Courtesy: Karen Smith)

Spirits raised, the forest green-clad Wolfpack turned their heads to their manager, Karen Smith, who smiled.

“Mission accomplished,” Smith thought.

Jenner had been battling a stomach ailment since October of the previous year. For months, Smith had been the ringleader in supporting her teammate, staying by Jenner’s side as he recovered from multiple surgeries and a medically induced coma.

“That's the kind of team we are. You know that everybody cares about everybody,” Smith said. “He was so sick that nothing was healing properly, and I went up to see him after the first surgery. I manage the team, so we're friends, but it's more like, I look at these guys now as like my kids. And I’ve got to take care of everybody.”

At 72 years old, Smith is the glue that holds the Wolfpack together, having been involved with the team since the NESHL’s original season. She's never far from her faithful service dog Koda, who climbs onto the ice after every Wolfpack game.

Smith didn’t grow up playing adaptive sports. The East Haven, CT resident found the community mid-life after her diagnosis of multiple sclerosis in 1990 at age 38.

Before her impairment, Smith was a lifelong skier and instructor. Smith worked with Gaylord Hospital to re-learn her beloved past-time through sit skiing, an adaptive sport that looks similar to piloting a canoe on ice.

In sit skiing, the athlete sits in a bucket made of fiberglass, with a set of outrigger skis attached underneath. The racer can proceed to balance and propel themselves forward with either a traditional or shortened set of ski poles.

Smith’s new skills in sit skiing led her to try other para-sports like wheelchair tennis. When she heard rumblings about a Connecticut-based sled hockey team starting up, Smith was up for the challenge. Joining forces with her friends from her wheelchair tennis program, the Wolfpack was born in 2004, rough around the edges in an era before the NESHL’s launch.

“As soon as they opened up in Connecticut. I was just like, let's go. I don't care what we're called. I don't care what our jersey looks like. You know, I was like yo, I'm going to play, and it's going to be awesome.” said Tyler Konvent, a 20-year Wolfpack veteran who like Smith, was an original squad member.

40-year-old Konvent, born with spina bifida, has had a passion for hockey since childhood. His family were long-time season ticket holders for the NHL’s Hartford Whalers, as his mother worked full-time at the Hartford Civic Center, known today as the XL Center.

While the Whalers had contemplated funding a sled program for kids like Konvent before relocating to North Carolina, his first exposure to the game was through an impromptu clinic in Massachusetts.

“I checked it out and skated around. And it was literally like the mighty ducks.” Konvent said. “They didn't have pads for us. They just basically strapped us into buckets and sleds.”

With initial sponsorship from Chariots of Hope, a Connecticut-based non-profit that refurbishes and distributes used wheelchairs, the Wolfpack purchased equipment and jerseys and relied on donated practice ice time in local communities. Eventually, the team would be fully backed by the Gaylord Hospital Sports Association, becoming one of the hospital’s fifteen adaptive sports teams, and Connecticut’s only sled hockey team.

“They’ve been great, we've been able to do so many more things because of their financial backing,” Konvent said, describing the new resources Gaylord provided. “It really feels like a family, not just a company behind us or a hospital behind us. They’re really a part of us.”

Back on the ice, despite being one of the senior-most members of the 'Pack, Smith chose to hone her craft as the team’s goaltender when no one else wanted to volunteer at a scrimmage. Eventually, she was selected to be the Wolfpack’s captain, as she was considered amongst the best keepers in the NESHL.

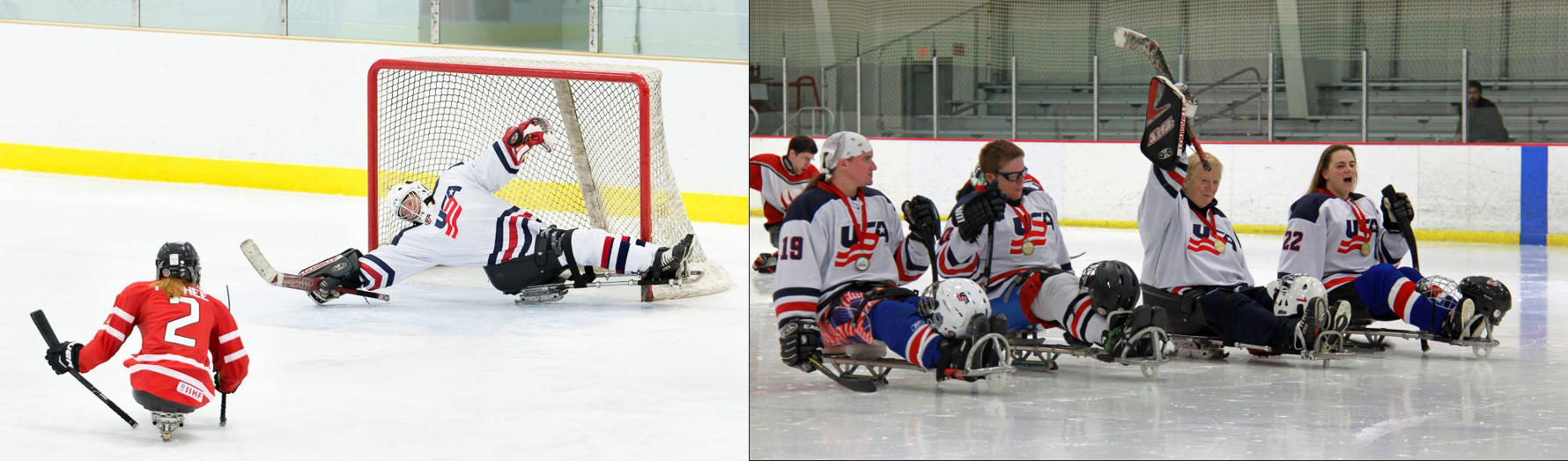

In 2014, Smith received a life-changing opportunity to play for her country on the international stage, earning the starting role for Team USA’s women's national team at the inaugural 2014 IPC Ice Sledge Hockey Women’s International Cup.

Smith’s efforts to defy time culminated in gold. The U.S. soundly shut down Canada 5-1 in the finals on Canadian soil in Brampton, Ontario.

“I was up there in age, I mean, at one point we had a 16-year-old [teammate], and I was 61, so we always joked about the fact that our ages were reversed in the numbers.” Smith said. “But being out on that ice and just hearing people up in the stands chanting ‘USA, USA, USA’. I mean, it gives me chills now to think about it because it just went right through you.” Smith said.

Smith makes an acrobatic save (left) and celebrates her gold medal victory with Team USA. (right) (Courtesy: Karen Smith/Michael A. Clubine)

Smith’s gold medal was just the beginning of the championship success for Gaylord. 2023 was the year of Connecticut teams taking home national titles, but the UConn Huskies and Quinnipiac Bobcats were not the only state squads in the title mix.

The Wolfpack became Connecticut’s third national champions of the year, victorious over NEP for the Adult Tier II National Championship at the USA Hockey Disabled Hockey Festival in St. Louis, Missouri.

“Every game, there was just a spark. Nobody needed to be motivated.” Konvent said. “That whole tournament, we were just playing as a team, where I don't think all the other teams were as cohesive as we were. It was just a cool experience to be a part of.”

Smith, a Quinnipiac University alumnus, was proud to stand alongside her alma mater as a Nutmeg state national champion but was headed towards a behind-the-scenes role as a manager. Over the years, Smith had had nine shoulder surgeries to keep the hourglass from running out, but in her early seventies, it was time to cheer on her chosen family from the bench.

After the game against the Sled Rangers was over, Smith orchestrated a post-game visit to Gaylord for the team to present a hand-sewn Wolfpack quilt to their friend, “Tiger”. The quilt knitted by his teammates was adorned with photos of Jenner’s on-ice adventures and logos from the Wolfpack’s national championship banner.

The visit was one of seemingly hundreds Smith made over a half year to keep a promise to Jenner to be there for her friend, no matter what.

Konvent (right) helps his teammates present the custom Wolfpack quilt to Jenner. (Courtesy: Karen Smith)

“I remember right before they took him out for his surgery. And this is something that you know that we would never say to each other in the past as hockey buddies. But he looked at me and said, 'please don't leave me'. I said ‘I won't. I'll be right here.’” Smith said. “Since that day [I was] there every single day.”

Two months later, Jenner was headed home. The Wolf Pack could breathe easier. A member of their family, their pack, was getting better.

Smith shared the news of Jenner's journey home on Facebook. (Courtesy: Karen Smith)

“There are bonds that I've created, where these guys feel like family. They're brothers and sisters. They're not hockey players or teammates. They're genuinely brothers and sisters,” Konvent said.

The NESHL is…a chance to build towards the future.

Larry Minei took a deep breath and pushed his sled slowly to the bench, taking his spot at the head of a huddle of blue, red, and white-clad players.

Minei is used to this kind of pressure. The huddle is his domain, the last chance to run the New York Sled Rangers through strategies ahead of puck drop.

As the team’s player-coach, he adjusts the game plan between shifts as a blue-line patrolling defenseman. At the same time, he compartmentalizes off-the-ice logistics, like when he’ll check the team into the weekend's hotel, and where to book dinner reservations that can accommodate a party with ten wheelchairs.

The arena's scoreboard buzzer sounded, ending the pregame meeting abruptly. Minei, confident, laid his stick down in the center of the huddle. His teammates followed suit.

Minei (second from left) sets the tone for the Sled Rangers with an impassioned pre-game speech. (Photo: Clever Streich)

“Rangers on three. ONE, TWO, THREE…” Minei shouted.

“RANGERS!” his teammates roared, raising the taped sticks proudly into the air and skating off for the faceoff.

The New York Sled Rangers are one of three NHL-affiliated sled teams playing in the NESHL, having returned to the league for the 2023-24 season after a multi-year reprieve to rebuild during the pandemic. The team was co-founded by Bill Greenberg and Victor Calise, a former commissioner of the New York City Mayor’s Office for People with Disabilities.

Ironically before joining the sled-bound Blueshirts, Minei grew up as an Islanders diehard. Regardless of allegiances, hockey was a constant in Minei's life, as he started to skate in local games from seven years old on before his health got in the way.

“At 14 years old, I lost a little use of my left leg, so hockey went out the window. Then I became permanently disabled after I had about 15 back surgeries. At the age of 20, I lost the use of both of my legs from surgery.” Minei said.

Minei has used a wheelchair since. He left behind the game he loved for a decade and a half, but at age 34, Minei met Anthony Fitzgerald, a teammate of Calise at the 1998 Nagano Paralympic games. Fitzgerald told Minei there was still a way to play hockey adaptively, as he invited Minei to practice with the Long Island Rough Riders sled team.

“I got on the ice the first time, and that was it,” Minei said. “The smell of the ice, like I know it's just the whole way your lungs feel when you're breathing on the ice. There's something about that that always was nostalgic to me. As soon as I got on it I was like, ‘oh, my god, I'm back’!

Minei took the next step when he again followed Fitzgerald to the Rangers sled hockey team, joining a then six-team NESHL in 2012. Minei would also have a new teammate, his wife Sara Tabor, who has used a wheelchair since falling in a shower and being partially paralyzed from the waist down. Tabor would also win gold with the U.S. at the 2014 IPC Ice Sledge Hockey Women’s International Cup alongside NESHL rival Karen Smith.

For the past eight years, Minei has solely been at the helm managing the team’s relationships with the NESHL, the NHL’s New York Rangers, and the Wheelchair Sports Federation, a not-for-profit providing the team with sponsorship and equipment donations.

Being an NHL-affiliated sled team, the Sled Rangers have a few unique perks, including ice time at the MSG Practice Facility in Tarrytown, NY, entry into the NHL Sled Classic, an annual tournament exclusive to NHL-affiliated sled teams, and the occasional opportunity to play between-period exhibitions at Ranger games in front of thousands at Madison Square Garden.

Other unforgettable interactions were opportunities for Rangers legends like Mike Richter, Marc Staal, and Adam Graves to strap into a sled and try their hands at adaptive hockey, playing alongside their sled counterparts. But for Minei, what made the work worthwhile were moments like February 6th. 2014.

For a few weeks after the NHL’s New York Rangers swept the 2014 Stadium Series in Yankee Stadium, the ice surface stayed up and was used for special community games. One night, the Sled Rangers were invited to play an outdoor exhibition against the Philadelphia Flyers sled hockey team.

While Minei’s Blueshirts came up short to the Broadstreet sled Bullies, a candid photo was taken of him and Tabor after the game.

“One of my favorite pictures of my wife and me and I have it framed up on my desk at work, it's the back of us sitting in our sleds. Nobody on the ice except us, and we're kind of looking out at Yankee Stadium, the lights and everything.” Minei said. “At that moment we were in awe of what we were doing. It's one of my favorite photos of the two of us, playing a sport that we loved.”

Minei and Tabor share a quiet moment on the Stadium Series ice at Yankee Stadium. (Courtesy: Larry Minei)

As the years passed after that chilly night at Yankee Stadium, the average age of the veteran Sled Ranger increased dramatically. Players in their 30s and 40s when the team was founded had become a decade older.

To bolster the team’s core, the Rangers began “calling up” players who are NESHL eligible, but primarily are members of the Wheelchair Sports Federation’s Junior Sled Rangers program that caters to players five to 18 years old.

One standout is the six-foot-three 16-year-old Max Wong, a NESHL rookie who helped the Junior Sled Rangers win a national championship at the 2023 Disabled Hockey Festival in Youth Sled Tier II. Max’s father, Elijah, has left an impact on the bench by managing equipment and assisting Minei in creating drills for practice.

“[I’m] just be able to be me out there,” Max said when reflecting on what he liked most about his first NESHL season. “As I've grown up, I’ve learned to manage my disability more. It's been easier and it's been more fun, growing up with everybody else on the team, just getting to know more people.”

Max’s family signed him up for the Junior Sled Rangers when he was four so he could make friends and stay active after being paralyzed at two and a half years old. Twelve years later, he’s the last original Junior Ranger of his age group from the inaugural 2012 season, as Max rose to become a leader and guide for younger members.

“When he first started, I recall him not even wanting to be on the ice. It was too cold,” Elijah said. “[But] he comes through in the clutch. He's not Michael Jordan yet, but you know it's good to see him wanting the puck when it's game time, or it's tied up, and he wants to get that winning goal. It's been a long time in the making for that.”

While Max hast kept his hand in with the junior and adult Sled Rangers, he’s also made a name for himself in wheelchair tennis. Max clinched two 2023 USTA national championships in the junior and co-ed adult divisions, despite coming into the field unseeded.

Max holds his dual USTA National Championships after becoming 2023's top junior and adult co-ed player. (Courtesy: WSF Sled Rangers)

Living in New York City, Max was introduced to the sport through clinics with the Wheelchair Sports Federation at the nearby USTA National Tennis Center in Flushing, Queens. After being graciously donated a custom-built wheelchair to play tennis, he was instantly hooked.

“The difference between [wheelchair tennis] and hockey is that it requires a lot more hand-eye coordination, and it's more self-reliant,” Max said. “In hockey, you can pass it off if you don't shoot too well. But tennis, it’s like you have to train yourself, otherwise you’re not going to make it very far.”

Max can be found on the tennis court practicing his backhand when he's not on the ice. (Courtesy: Max Wong, Toalson USA)

As he approaches the college search, Max and his family hope that he can continue to pursue his adaptive sports dreams, but also receive a high-quality education that will land him a job.

“The thing about New York City is, we were extremely fortunate that there was a team here,” Max’s mother Claire said. “Then to have an adult league, basically for our kids to grow into and to be farmed into. It's so important to the disability community in general that they always have a place to move on to next.”

The NESHL is…an outlet to cope and improve one’s life.

The puck was sharply flung into the corner boards as the Wildcats pinned the possession against the wall. A USA Sled Warrior wearing number six, dressed in all black from helmet to sled barrels his way through bodies to blast the puck down to the other end for the clear.

Underneath his helmet, former Marine lance corporal Mike Martinez grinned and cut back to the bench to end his shift. When he’s in his sled, he’s in his element.

“I just love to go on the ice. Go fast. Hit. Try to score some goals.” Martinez said. “I normally play center and one of the guys we played against [that] weekend called me the ‘human wrecking ball’, that I probably have the most hits and penalty minutes on my team by far.”

Martinez did not grow up watching hockey in Arizona because in his words, “ice wasn’t a thing for us". However, he did have a knack for sports, as he ran track and played football, soccer, and baseball at Prescott High School. After graduating, he took the opportunity to enlist in the Marine Corps and register for the Junior Reserve Officers' Training Corps.

Soon his desert surroundings of Arizona were replaced by the arid war zone of Afghanistan, where he fought for his country from 2008 until March 11th, 2010, when Martinez’s life was changed forever on a patrol mission.

“It was a four-hour firefight we were in and on the way back, you're just smoked. You're not thinking, you're not paying attention that much. So, while we were walking through this poppy field, I stepped on an [improvised explosive device].” Martinez said.

Martinez was five months into his deployment in Afghanistan before being wounded. (Courtesy: Mike Martinez / Homes for Our Troops)

Ten minutes after the explosion, Martinez was helicoptered to a medical unit, where he underwent a four-day marathon of surgery at Camp Bastion Field Hospital in Landstuhl, Germany. Then, he was whisked state-side to Bethesda, Maryland to receive further treatment at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, one of the biggest military hospitals in America.

It was determined that Martinez would need both of his legs to be amputated above the knee and that he would have to recover from a collapsed lung, a broken pelvis, and scarring. Martinez endured forty more surgeries and a year and a half of physical therapy. His goal? To get out as quickly as he could.

“I'm just like, ‘I'm done with the hospital. I'm tired of this, get me out of here’,” Martinez said. “It's pretty much just working out to get your life back and get some type of normalcy back.”

After amputations on both his left and right legs, Martinez re-learned to walk by gripping parallel bars. (Courtesy: Mike Martinez / Homes for Our Troops)

Mike’s mother Sharon and father Larry supported him throughout his recovery as he adjusted to the pain of maneuvering with two prosthetics. He was progressing towards his new day-to-day life, but staying active regularly was another challenge.

During Martinez's rehab, a member of the USA Warriors, Paul Schaus, reached out to see if he wanted to join other wounded warriors in a sled for a change of scenery. It was a hard pass for Martinez at first.

"[He] came to me like, 'We've got this team. We need some players. Would you consider coming playing?'" Martinez said. "I told him, no. Why would I ever want to do this?

The Warriors, based out of Walter Reed Hospital, has provided a therapeutic and recreational outlet for veterans like Martinez to try sled or stand-up hockey since the organization’s inception in 2008.

The Warriors developed into a fully-fledged member of the NESHL in 2013, a squad comprised of military veterans from all five service branches. The program’s success has spawned several sister teams in the NESHL, the Ohio Warriors, and the New England Warriors, which serve veterans who want to play sled hockey in regions outside Maryland and Washington D.C.

Despite his initial reluctance to try the game, his passion was forged four years later when he watched Schaus and the U.S. national sled hockey team win gold at the 2014 Sochi Paralympics.

"I watched U.S.A. beat Russia, and I'm like, 'oh, this is the greatest thing ever'," Martinez said. "I had been working out a little bit, but I didn't have something to put it towards. So after that, I emailed the Warriors."

A familiar sense of comfort and community returned to Martinez's life as he got involved. Just like in service, he was surrounded by a team of veterans who understood experiences like his and shared the same love of adaptive sport.

"When you get around other people that have had those similar experiences

then you could talk about things," Martinez said. "We can just come together, talk things out, have fun, and still have that community that we had before, that I don't really think you can find outside of the military."

The common bonds in a life of service may be what brought Martinez to the rink. Still, in the landscape of the NESHL, a league based on improving the quality of life for its players, no unit may be more tightly bound and focused on moving forward together than the USA Warriors.

"That's our outlet. That's kind of like we used to do in the military. We get to go out and let out some aggression. Have some fun and play that team sport." Martinez said. "We still get to come together and keep that mindset that we had in the military going with being on the ice. The community keeps what we had alive, just in a new setting.

Martinez focuses ahead of the 2024 Hockey for Heroes Charity Game in Annapolis, MD. (Courtesy: Shawn Stepner/WMAR Sports)

~

Clever Streich graduated from Quinnipiac University in 2024 with a master's of science in Sports Journalism and in 2023 with a bachelor's of arts in Communication & Media Studies. He is an Olympic Production Assistant with NBC Sports in Stamford, CT, and looks forward to contributing to the Paris 2024 Olympics and Paralympics this summer. You can find him on Twitter @CleverStreich and Instagram @thecleverstreich.

This site is for educational purposes only. Copyright Disclaimer under Section 107 of the Copyright Act of 1976: Allowance is made for “fair use” for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, education, and research.

Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing.

All rights and credit go directly to its rightful owners. No copyright infringement is intended.